Apprenticeships: At the crossroads of education and talent development

President and CEO, Ascend Indiana

Vice President of Consulting and Co-Founder, Ascend Indiana

If Indiana sent its business, education and public and private sector leaders to Switzerland to explore the world’s most promising ideas around talent development, would it profoundly change the way the Crossroads of America cultivates its talent pool? Could it help these leaders envision a new intersection where employers work more closely with educational institutions to co-develop the future workforce? It might, if they remain open to the possibilities.

Switzerland shares many of Indiana’s qualities, including a similar population size, a majority of small- to medium-sized companies, a mix of rural and urban communities, a similar constitution and a system of free enterprise with a high concentration of life sciences companies like Roche Diagnostics. Despite having few natural resources, Switzerland’s emphasis on developing human capital has led to a per capita annual income greater than $70,000 (U.S. dollars).

A central element of the Swiss economy is a philosophy focused on the practical experience that both students and adults derive through work. Beyond preparing high school students for in-demand jobs, it creates easily understood pathways. These pathways work for both young adults and life-long learners who may pursue advanced education or training or those who want to switch from a vocational to a professional pathway. And these pathways provide options – whether through the traditional college degree track or work-based learning programs with well-defined advancement opportunities – to create economic mobility for every student and adult, regardless of demographics or educational experience.

Escorted by the Indy Chamber in partnership with Ascend Indiana, a group of Hoosier leaders will embark on a Leadership Exchange (LEX) trip in September to immerse themselves in the Swiss youth apprenticeship model embedded in their culture.

Last fall, Ascend Indiana and EmployIndy analyzed the state's talent supply and demand, creating a presentation from which the figures in this article were pulled. Click on any of the graphics below to access more data and learn more about Indiana's talent supply and employer demand.

Indiana’s urgent need for change

Why is the successful Swiss youth apprenticeship model attractive to Indiana leaders? Our approach to developing current and future talent is beginning to shift. Current pathways in Indiana between K-12 classrooms and postsecondary education simply do not work for enough students. Combine that with too few Indiana high school graduates enrolling in higher education. Postsecondary enrollment rates stood at 65% of 2015’s Indiana high school graduates. That rate declined to 53% in 2020.1 Of those who do enroll, an insufficient number pursue degrees in fields that align with high-demand jobs. Even fewer complete their degrees, and many of those who do graduate choose to leave Indiana.

Significant racial disparities

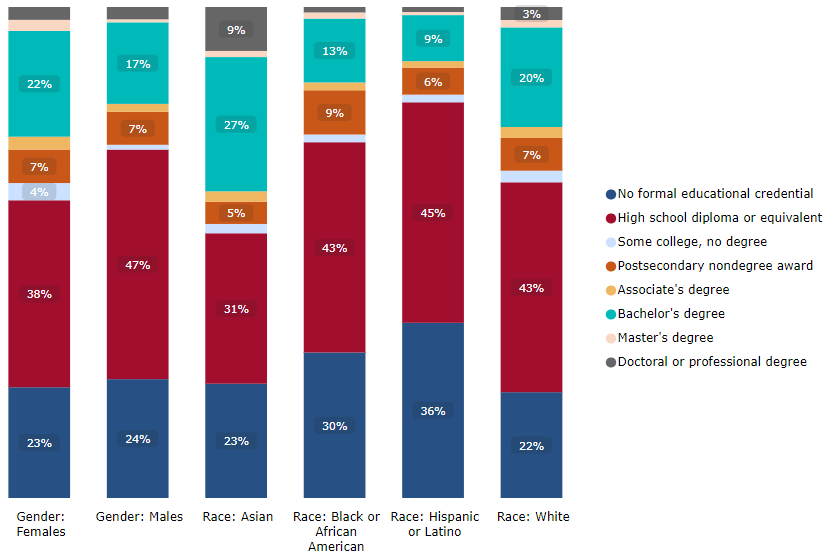

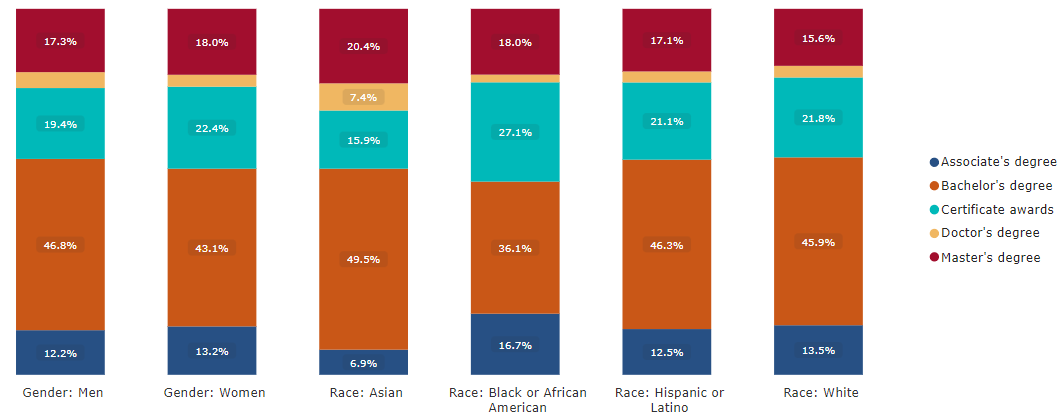

When educational attainment data is disaggregated to reflect demographic factors, the status quo becomes more alarming. Existing race and gender gaps are exacerbated through workforce outcomes, limiting the opportunities for people with less education to earn good wages. Figure 1 shows that Hispanic or Latino and Black employees are far more likely to fill jobs that require no formal educational credentials. Throughout Indiana and within Marion County, Hispanic or Latino and Black students are less likely to receive any type of high school diploma.

Figure 1: Indiana employment in occupations by entry-level education, 2020

Note: This visual uses entry-level education requirements developed by USDOL in combination with Lightcast occupation and demographic data.

Source: Lightcast™, 2022. Release 2021.4

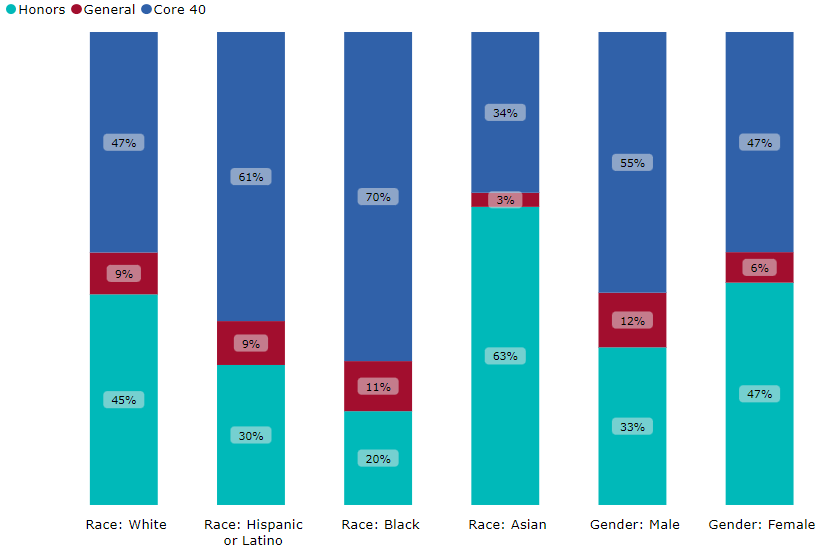

Among male Black and Hispanic students who graduate, most receive general or Core 40 diplomas, compared to white, Asian, and female students, who disproportionately earn honors diplomas (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Diploma type earned by demographic group high school graduates, 2019-2020

Note: This visual uses entry-level education requirements developed by USDOL in combination with Lightcast occupation and demographic data.

Source: Indiana Management Performance Hub

Despite existing college readiness programs, just 11% of Black students and 16% of Hispanic students completed college degrees at Indiana public institutions, compared to 25% of their white counterparts.2 Figure 3 shows that overall, Black students are less likely to complete a bachelor’s degree than white or Asian students.

Figure 3: Degree award level composition of Indiana postsecondary graduates by demographic group, 2019-2021

Note: Data represent degrees awarded at all Indiana postsecondary institutions. The certificates category includes all certificate types, including short-term, long-term and post-bachelor’s/master’s certificates.

Source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS)

Work-based learning programs are often instrumental in helping students identify what they want to do and what they are good at as they apply lessons learned in high school classrooms to the workplace, creating a vital connection between education and real-world job readiness. Yet data shows that students who are typically left behind by traditional systems have even less access to these programs than their peers. For example, Black, Hispanic or Latino and female high school graduates are the least likely to obtain paid internships.3

Growth in employer demand and shrinking supply

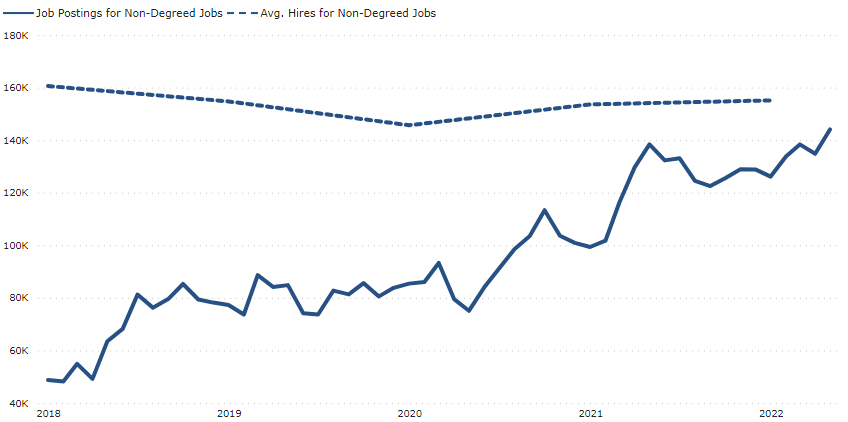

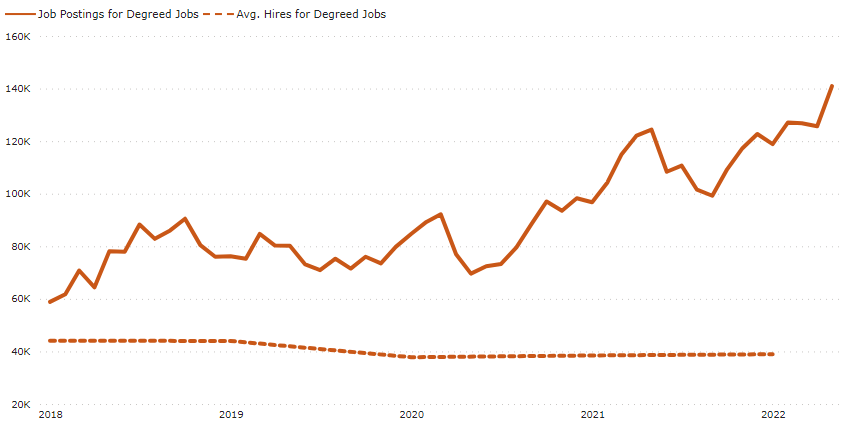

Examining proven workforce development strategies is critical for Indiana’s economic health, given the sheer number of employers struggling to fill positions. Since the summer of 2018, the average number of new hires per month has remained flat or declined slightly, while the number of job postings more than doubled during the same period (see Figure 4). The demand is especially high for positions requiring some type of postsecondary credential.

Figure 4: Indiana non-degreed and degreed job postings and average monthly hires

Note: Non-degreed jobs include jobs requiring no degree, a high school diploma or some college. Degreed jobs include postsecondary non-degree awards, associate degrees, bachelor’s degrees, master’s degrees or doctorates. Average hire data is annualized, while monthly job postings are monthly.

Source: Lightcast™, 2022. Release 2022.2

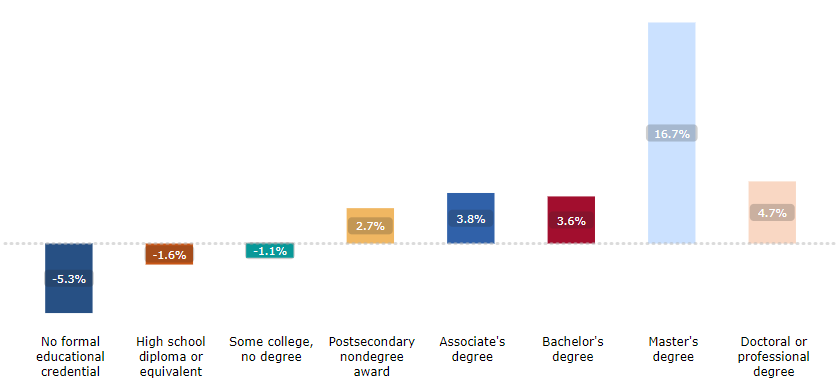

As the COVID-19 pandemic triggered rapid shifts in both society and the economy, our state’s demand for non-degreed talent slowed significantly, while the demand for degreed talent has continued to accelerate. Economic forecasts for Marion County confirm jobs for which only a high school diploma (and, perhaps, a few college credits but no degree) is required will continue to decline for the foreseeable future (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Projected percent change for jobs in Marion County by education level, 2020 to 2028

Source: Lightcast™, 2022. Release 2021.3

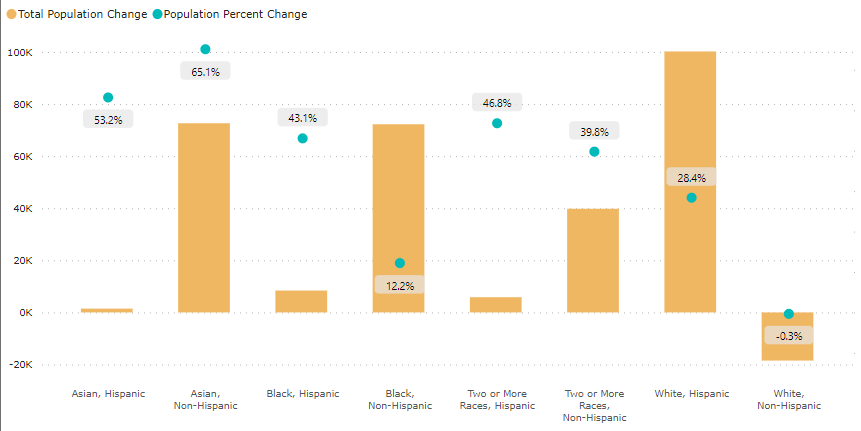

Another challenge for Indiana employers: an aging workforce. The Baby Boomer population largely transitioned to retirement age between 2011 and 2021, while Generation X is beginning to show declines in labor force participation in the 40-to-54 age group. At the same time, Indiana’s population is becoming strikingly more diverse, with population growth during the same period driven by non-white individuals, primarily Asian, Black and Hispanic populations (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Indiana population change by race/ethnicity, 2011 to 2021

Source: Lightcast™, 2022. Release 2022.3

Broad support for initiatives

While their motivations for doing so may differ, educators and employers both embrace the goal of providing high school students with purposeful exposure to meaningful career opportunities. Despite pockets of strong programming across the state, these efforts do not result in a system that translates employers’ workforce needs at the occupational level into our K-12 and higher education systems in a way that most benefits students.

Youth apprenticeship, Swiss-style

The central component of the Swiss effort is youth apprenticeships, although it vastly differs from the American conception of the term. In the U.S., apprenticeships typically refer to a narrow adult training program for a specific technical trade. The Swiss approach involves high school students building their studies around high-demand jobs designed to evolve into full-time work when they matriculate either at their host company or to another company. Unlike U.S. high school internships in which participants do little more than observe adults handling tasks, their Swiss counterparts, serving in youth apprenticeships, have paid roles within their employers’ companies, performing the same tasks as their adult co-workers.

The Swiss program involves companies in every major business sector, from health care to financial services. It is overseen by a three-way partnership: private sector, government and the education system. An important additional partner includes their national chamber of commerce organization, acting as an intermediary between the business and educational communities. The intermediary connects job-seeking students with employers, monitoring the relationship to ensure it meets both parties’ needs, and designing curricula to ensure positive employment outcomes for both student and employer. In addition, intermediaries collaborate with policymakers to develop and enhance nationwide occupation standards frameworks. In Switzerland, 70% of students each year choose to participate in a youth apprenticeship.4

Infrastructure needed

While the benefits of introducing high school-age students to the workforce with the optimal level of support are obvious, a Swiss-style effort requires an infrastructure that does not yet exist in Indiana.

This system requires intermediaries capable of identifying and connecting individuals to apprenticeships and jobs, co-developing training between employers and education providers and supporting the development of a public policy framework to ensure the system is responsive to employer and student needs. Indiana already has several intermediaries supporting dimensions of this system.

A successful example of the youth apprenticeship concept is operating today with more than 40 Indianapolis-area employers and 113 high school students participating (350 have said they are interested) from 14 different high schools. Also, there are nearly 500 youth apprentices experiencing work-based learning that is being coordinated through other leading intermediaries across the state.5

Central Indiana’s successful effort

In 2020, Ascend Indiana (an initiative of the Central Indiana Corporate Partnership) and EmployIndy (Marion County’s workforce development board) launched a joint effort called the Modern Apprenticeship Program (MAP). High school students emerge from the three-year program with a high school diploma, college credits, relevant credentials and paid professional experience. Employers in multiple high-demand industries, among them information technology, financial services, health care and advanced manufacturing, currently participate.

MAP and similar programs require local employers willing to integrate youth apprenticeship into their operations. For Dr. Michelle Mitchell, the manager of programs and workforce development for Ascension St. Vincent, it was a desire to grow the next generation of health care professionals in a post-pandemic era that drew her to the program.

“All of the high school students go through a rigorous selection process and are interviewed, just as we do with our candidates who are high school graduates,” Mitchell noted.

“Applicants are scored, and the highest scores are offered a position in MAP. We have a modified work schedule because of their school day, but they are employees who are learning which skills and abilities are essential to becoming successful within our workforce. They’re learning about patient care and safety during the school day and practicing what that looks like when they work with our care teams and patients. They can see the potential for a lifelong career in health care.”

Mitchell is also quick to dispel any misconceptions that employers have to “babysit” the students. In fact, she says it is quite the opposite.

“One of the challenges in launching MAP was ensuring students have a real-life, hands-on experience as they work within our health system,” she stated. “Our supervisors welcomed opportunities to influence high school students and after the first cohort of high-achieving students, our supervisors can’t imagine what it would be like without these apprentices.”

MAP apprenticeships span from the student’s 11th-grade year to beyond graduation, with an increasing number of weekly work hours over the three-year span of the program. Each apprentice follows a training plan addressing foundational competencies such as soft skills, knowledge needed across the particular industry and skills needed for success in specific roles. Related high school and college courses support the work experiences, helping youth apprentices earn the employer’s preferred industry-recognized credentials.

Supporting diversity efforts

Prioritizing diversity and equity within the workplace benefits from the youth apprenticeship approach. The structure delivers practical ways to allow students to overcome economic challenges by providing income while they learn. Currently, 88% of students in MAP identify as students of color, 64% identify as young women and one-third identify as coming from low-income backgrounds.

That’s important, because a sometimes-voiced concern about the Swiss approach is the mistaken belief it dooms disadvantaged students by channeling them into careers with little or no opportunity for growth. In reality, programs such as MAP not only expose students to real-world jobs, but also create awareness of advancement opportunities through additional education and training. Higher education partners with initial concerns about losing potential students quickly recognize they’ll serve students in the foreseeable future, when students know what they want to study and why they want to study it, which will likely lead to greater academic success.

Indiana’s inflection point

As Indiana employers contend with a changing labor market, they can exert greater control over talent development through proven models such as the Modern Apprenticeship Program. Other entities can play roles to help employers succeed. For example, intermediaries such as Ascend Indiana can play a critical role as convener and translator, helping both employers and educators find common ground. The education system can use employment input to adjust curriculum, so students are better able to obtain practical knowledge and career skills, moving them into self-sustaining jobs and allowing them to contribute to the local economy. Finally, policymakers can create the infrastructure needed to change the system. This effective approach to collaboration will make Indiana a place of economic opportunity for all.

To learn more about the Modern Apprenticeship Program, visit www.indymodernapprenticeship.com.

For more information on Indiana's talent supply and demand, check out Ascend Indiana and EmployIndy's presentation on Indiana's evolving labor market.

Notes

- Indiana Commission for Higher Education. 2022. “Indiana College Readiness Report 2022.” https://www.in.gov/che/files/2022_College_Readiness_Report_06_20_2022.pdf

- Ibid.

- Strada Education Foundation. 2022. “The Power of Work-Based Learning.” Figure 4. March 16, 2022. https://stradaeducation.org/report/pv-release-march-16-2022/

- Embassy of Switzerland in the United States of America. “Vocational Education and Training & Apprenticeships.” https://www.eda.admin.ch/countries/usa/en/home/representations/embassy-washington/embassy-tasks/scienceoffice/vocational-education-and-training_apprenticeships.html

- Ascend Indiana and EmployIndy. Modern Apprenticeship Program statistics. August 2023.