A short history of the citizenship question

Deputy Director and CIO, Indiana Business Research Center, Indiana University Kelley School of Business

The 2020 census has been in the news recently because of the decision to re-incorporate the so-called “citizenship question” on the short form. Some of us still call it a short form because prior to 2010, there were always two forms—the short one had a small group of questions that went to every household. The long form had more questions and went to a sample of households.

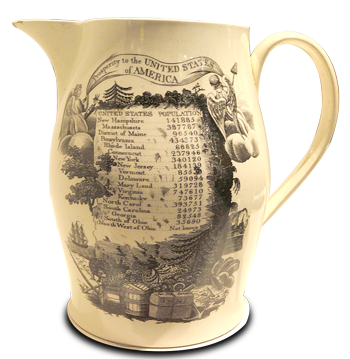

Made in England for the American market, this creamware jug

commemorates the first census of the United States taken in

1790. Source: National Museum of American History

We have less than two years before “Census Day” arrives, that day of counting every person in the United States (including its territories). It sounds simple—count every person living in the United States. But since the first census in 1790, it has been a difficult and time-consuming process, one that once involved U.S. marshals riding out on horseback to interview every household and now has evolved to what we can do in the spring of 2020: answer the census via a secured web connection.

The decennial census long form lives on in the American Community Survey, which goes to a sample of about 4 million households every year—helping to reduce the response burden but still yielding much-used data on education, income, housing—and yes, it even asks about citizenship and naturalization.

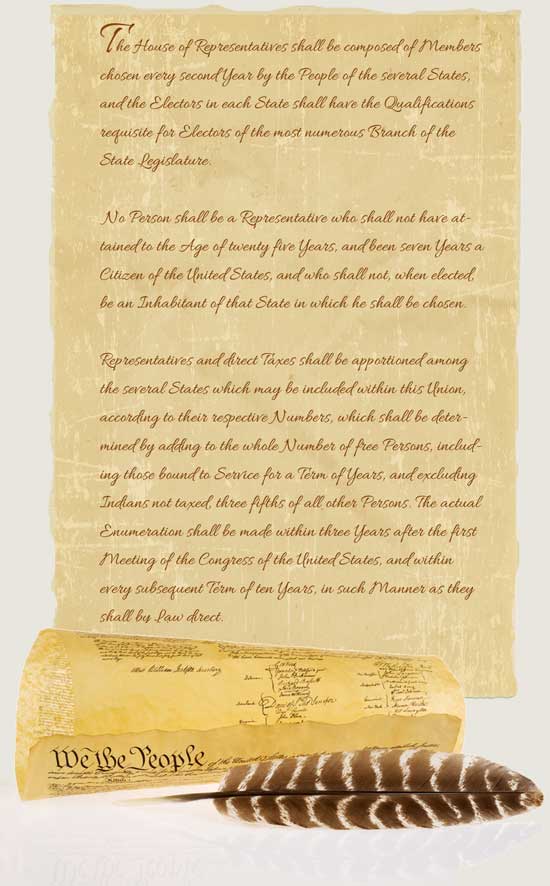

We are constitutionally bound in this country to have the federal government conduct a census at least once every 10 years. Here is the original constitutional clause in which the census (enumeration) is established:

Source: Article 1, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution

This section was later amended by the 13th (1865) and 14th (1868) amendments to the constitution. The heinous practice of slavery was part of the original constitution as were the methods by which the enslaved would be counted. As you will see as you read on and if you turn to the actual list of questions for each census, there were quite specific questions about the slaves held by households on the actual scheduled list. (See "Black and White in Indiana" from an earlier issue of the Indiana Business Review for more on the subject of the census count and Indiana slaveholding practices.)

The first count of persons living in the newly organized and constituted United States of America occurred in 1790, as required by the constitution to count “all persons.” At the time, U.S. marshals were the primary census takers, going from home to home and asking for the number of:

- Free white males under age 16 and ages 16 and older

- Free white females

- Other free persons

- Slaves

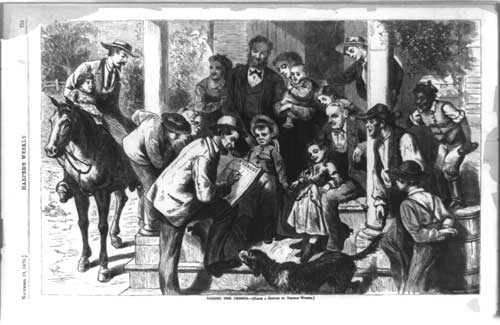

Wood engraving print by Thomas Worth of a census taker talking to a group of men, women and

children—including an African-American. Published in Harper's Weekly, Nov. 19, 1870.

By 1800, questions were added to get more age detail on “free” and “white” males and females, along with the other questions posed in 1790.

And as it so often goes, the number of questions began to grow; in 1810, questions about manufacturing—with 25 broad product categories encompassing more than 220 kinds of goods produced—were added. This was considered of such importance that Congress authorized $2,000 for the Treasury Department to prepare a statistical report on it.

It wasn’t until the 1820 census that a question about “foreigners not naturalized” was asked.

By 1850 (sixty years after the first census), more than a dozen questions were asked across two “schedules”—one for free persons and one for those persons who were considered slaves. Yes, that would not stop until the 1870 census.

The 1850 census was the first to ask respondents their place of birth, their real estate value and their profession. The census also asked about literacy and who in the household could not read or write. Subsequent censuses would ask about naturalization until it was dropped in the 1960 census.

It should be noted that the census questions multiplied decade after decade. During the mid-1900s, the Census Bureau began taking on more and more surveys—“sampling” the population rather than asking everyone. These surveys supplemented what Congress wanted to know about the people living and working in their communities.

There are some resources regarding the census questions and the actual images of census questionnaires over the years.

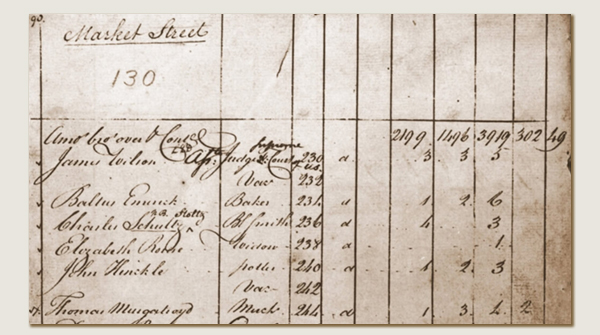

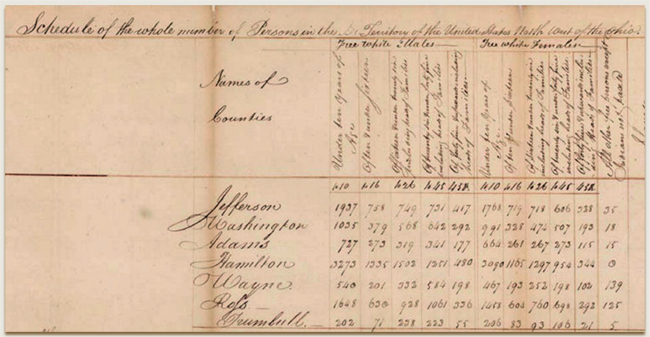

Here is an image from a “schedule” from the 1790 census (at the time, Indiana was part of the Indiana Territory and was not counted as a state until the census of 1820).

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

Here is a much better organized schedule or form in 1800—keep in mind, all of this work was done by hand, written by clerks and scribes.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

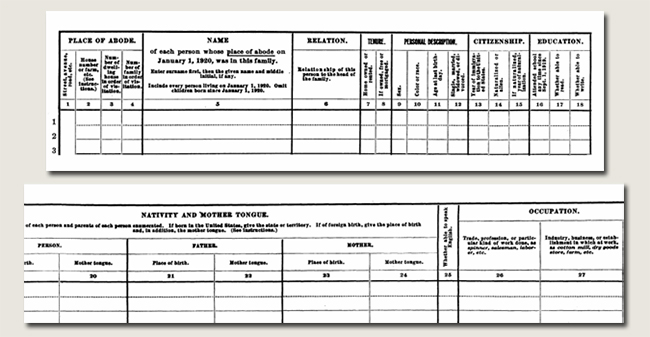

By 1920, the forms used by the census takers or enumerators were all printed by typeset, but the census taker wrote in all the answers as they interviewed the householder. Legible handwriting was essential!

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

For the 2010 census, there appeared only 10 questions per person on the census form:

- How many people were living or staying in this house, apartment or mobile home on April 1, 2010?

- Were there any additional people staying here April 1, 2010, that you did not include in Question 1?

- Is this house, apartment or mobile home: owned with mortgage, owned without mortgage, rented, occupied without rent?

- What is your telephone number?

- Please provide information for each person living here. Start with a person here who owns or rents this house, apartment or mobile home. If the owner or renter lives somewhere else, start with any adult living here. This will be Person 1. What is Person 1's name?

- What is Person 1's sex?

- What is Person 1's age and date of birth?

- Is Person 1 of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin?

- What is Person 1's race?

- Does Person 1 sometimes live or stay somewhere else?

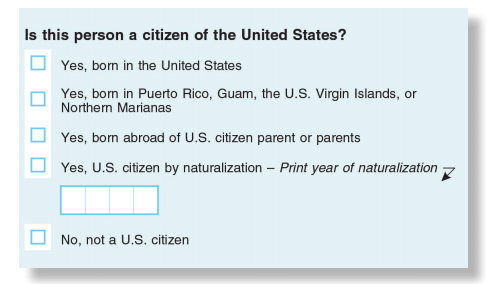

We will all receive notification that the next census is coming during the following 18 months, with news articles, posters, web ads and other means of letting us know this once-in-a-decade opportunity and requirement is here. The questions to be asked as part of the 2020 census will include age, sex, ethnic origin, race, household relationship, whether the housing unit is owned or rented—and, whether or not the person is a citizen of the United States:

Source: U.S. Census Bureau

The full set of questions, and how they are presented, can be found in the Questions Planned for the 2020 Census and American Community Survey booklet from the U.S. Census Bureau issued just this past March.

Indiana and its communities are already engaged in the 2020 census as they participate in a special program to review the address list the Census Bureau will use and to ensure it is complete and accurate. We are also gearing up for promotional efforts, since ensuring that folks respond by answering those questions is critical to the complete count. The Indiana Business Research Center at Indiana University has maintained a Census in Indiana website for many years and has updated it with the latest news and information to help Hoosiers navigate this huge event of counting the more than 6.7 million people in Indiana.